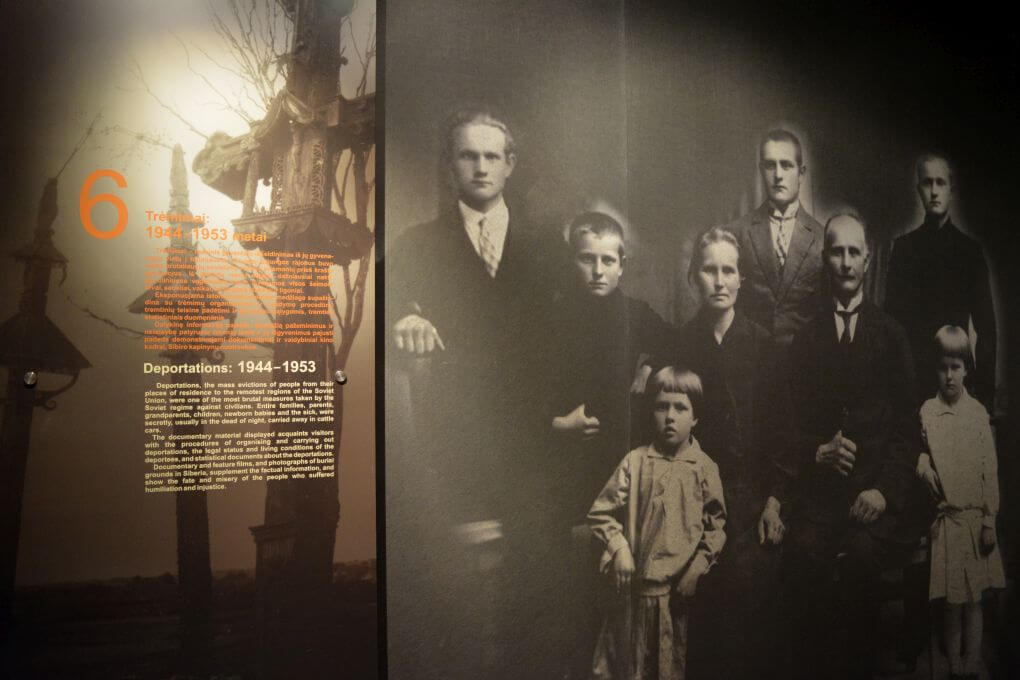

Deportations: 1944–1953

Pupils, students and pensioners (with ID) – 3 €.

Main Information

This part of the exhibition tells the story of the deportations carried out by the occupation authorities in Lithuania – the mass expulsions of the population from their places of residence to the most remote areas of the Soviet Union. Life in exile differed from life in a forced labour camp in that the deportees had greater opportunities to form communities, celebrate national and religious festivals, send their children to school, acquire property (e.g., a house with a small plot of land for a vegetable garden), and have less severe restrictions imposed on their freedom of movement. Nevertheless, the deportees also suffered a great deal of moral and physical hardships.

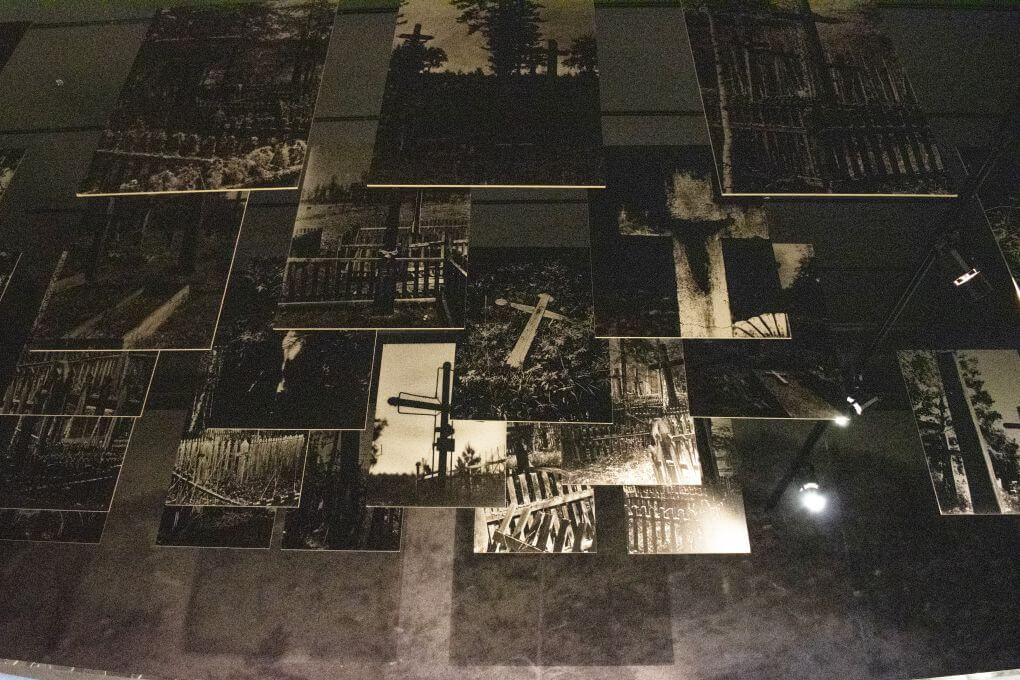

The historical documentary material on display describes the procedure used for organising and carrying out the deportations, the legal status and living conditions of the deportees, and the statistics on the deportations. Documentary and feature film footage and photographs of Siberian cemeteries show the painful fate and experiences of people who suffered humiliation and injustice.

Organisation of deportations

After the war, arrests and deportations of Lithuanian citizens resumed. The aim was to remove groups of the population opposed to the occupying forces from the country, confiscate their property, intimidate people into submission to the communist dictatorship.

The first to be deported were the families of participants in the armed anti-Soviet resistance and their supporters, convicts in hiding, and peasants who refused to join collective farms. The property of the deportees was confiscated and distributed. The deportations were orchestrated by special commissioners from Moscow. Together with the leadership of the repressive agencies of the LSSR, they drew up detailed plans for the deportation operations, estimating the number of operatives, internal and border troops, trucks, train wagons, and approving operational maps and charts.

The deportations were carried out in secret. People had 1-2 hours to prepare for deportation. People brought to the railway stations were put into freight (cattle) wagons and kept there for a few days until all the people to be deported had been rounded up. In the stuffy wagons, which were completely unsuited for the journey, the deportees would spend several weeks or even a month without hot food or medical assistance. Those sent to particularly remote places still had to transfer to barges or open trucks. Babies and the elderly died during long and exhausting journey.

The deportees’ property, family situation and living conditions were different from those of the prisoners, but their freedom was also severely restricted. Deportees were forcibly accommodated and employed in places designated by the Soviet authorities, the so-called special settlements. They had freedom of movement within these settlements but were not allowed to change their place of residence or work, to leave the settlement without the permission of the commandant, and they had to report to the NKVD commandant’s office every two weeks or every month. Unlike prisoners, deportees were paid for their work. They were allowed to correspond (subject to censorship) and receive parcels.

Lithuanian exiles were turned into a cheap workforce deprived of any rights. People who were exiled to forested areas worked in the taiga, cutting down the forest, building and driving rafts, and collecting sap. In the frosty Arctic, exiles fished, and in Altai Krai and other places of exile, they worked on Soviet farms. In the desert of Kazakhstan, people exhausted by heat and thirst built a road, and in Tajikistan they worked on cotton plantations. Exiles worked at construction sites, sawmills, brickworks, or wherever cheap labour was needed.

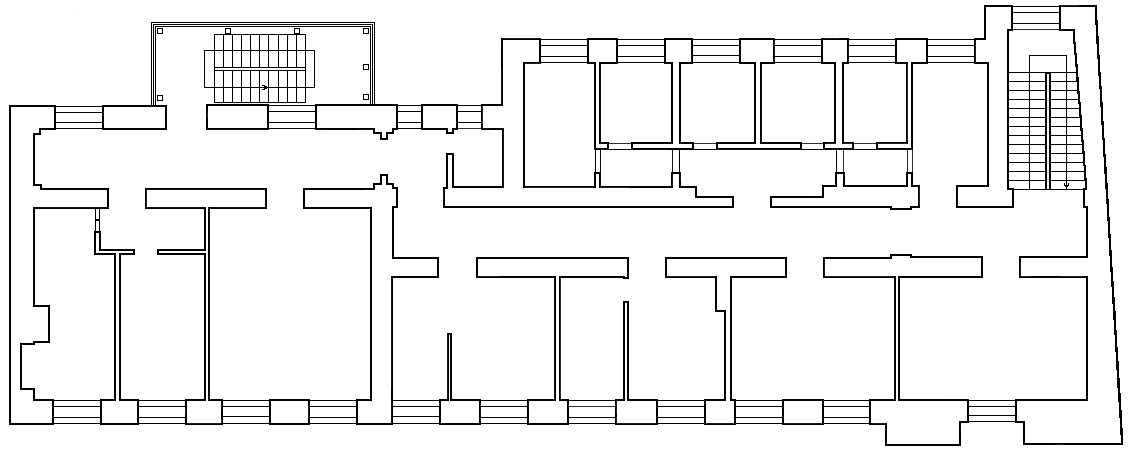

Exposition Location

Exposition „Deportations: 1944–1953“

Location: Second floor